The Roar

by Rachel Jade Rees

based on a true story

Miriam reached the top of Jericho Forest just as her calves began to cramp. The valley that led to Manapouri lay beneath. She’d be at the lakeside village safe and sound by sundown if she carried on.

She flew downhill toward Whare Creek, her red windbreaker flapping in the air. There was nothing but wide-open space and mountains on either side. It was a welcome view after being enclosed in the damp, darkened folds of mountain beech and pine, her quivering legs pushing her bike uphill for two hours. She had embarked on this bike trip to prove to herself that the world, and the men in it, were good: that her fears were just shadows from the past.

Jericho Lodge sat on the flat, beneath Brunel Peaks, a kilometre from the forest wall. Miriam peddled over to the faded business sign, awkwardly dismounted, her calves, thighs, and hips groaning in relief. A late March breeze trailed across her cheeks and danced over the grasslands, sending a cascade of movement and a whistling sound upward from the sunlit valley floor.

Three days earlier, at the Thornbury Tavern near Riverton, she’d met Dennis. A jovial man, mid-sixties at a guess, with balding hair and gold-rimmed glasses straight out of an eighties cop show. He’d offered her a bed for the night should she be passing by late in the day. Dennis was the manager and groundskeeper of a lodge on the Manapouri-side of the “Takkies,” hardly used except for the odd conference or school group. He’d be there for the next couple of weeks.

She pushed her bike over gravel toward a stand of harakeke at the entrance to what looked like the main building—deserted, just as Dennis had said. A row of farm sheds on her left stood empty. The long, covered walkway to the main building waited as if in anticipation of some movement, any movement, along its weathered planks. From Miriam’s vantage point, the Takitimu Mountains dominated, each serrated peak silhouetted against the vast blue sky above.

The afternoon light cast an eerie glow over her shoulder as she un-clipped the hook from her left pannier. Places and lands like these made her feel uneasy. They felt lonely and untamed in their isolation. But something else stirred beneath her discomfort: a recognition, as if the mountains were watching her. She distracted herself with unnecessary re-sorting, turning around when the wind got up to see if anyone was behind her. Spooked, she decided she’d carry on. There was plenty of light in the sky and blood glucose in her legs. She’d treat herself to a decent meal. Sink into a comfy bed with a hot water bottle and her journal. End the tour on a high.

The sound of tyres on gravel broke her thoughts. It turned into the sound of a dirt-covered ute. She looked up to see the figure of a man in the driver’s seat. Gold-rimmed glasses covered his eyes. The ute stopped short of the nearest shed, the door flung open, and out stepped Dennis, a look of surprise on his face.

“I expected you yesterday,” he said. “I figured you must have carried on through.”

He smiled brightly as he laboured to the back of the ute, reached in and pulled out two full plastic bags. “Could you grab the beer?”

Miriam breathed in as she pulled the flap over her pannier bag. She hobbled over to the ute and grasped a box of Speights with her thumb and forefinger like you would a tenpin bowling ball.

“I was just thinking I might carry on,” she said, limping after Dennis, who was halfway along the walkway, his biceps taut and knuckles white from the weight of food inside thin-handled bags.

“Bit late, ain’t it?” he replied with a smile. “You can stay in any room you like. Bangers and mash for dinner.”

Miriam knew she had to be decisive. The thought of a comfy bed and meal without the two-hour push to Manapouri clinched it, especially after the night she’d had before. She’d get a good night’s rest, enjoy this man’s hospitality, and cycle on at first light.

Miriam and Dennis sat in a pair of faded Lazyboy chairs. A small table between them provided enough space for the TV remotes and two bottles of Speights. They ate sausages, spuds, and mixed veggies spread with packet gravy while watching the news. Light conversation broke the silence between ad breaks. Dennis lived in Riverton with his wife, but spent more weeks at the lodge than there. Dennis and his wife didn’t have much in common these days, and he preferred it here, anyway. Especially during The Roar.

She’d heard deer hunters the night before at Lake Monowai. Initially, the hum of a boat engine sploshing along the southern arm, the revving increasing the deeper into Fiordland National Park it advanced. Just before dusk, she’d noticed a white Toyota Hilux parked down one of the forestry tracks that branched out from the main road. Much later, buried inside her sleeping bag on hard ground, she’d heard gunshots and loutish voices rebounding across the forest walls. The sounds had echoed longer than they should have, as if the forest itself was amplifying them, storing them in its memory.

She was on her bike, cycling the endless stretch of gravel back to Borland Road before the sun cast its warmth on the day and her mind.

Time slowed down a notch. She regarded Dennis with suspicion; noticed each time he took a swig of his beer.

“Have you ever been deer hunting?” he asked. Miriam shook her head and replied no. She told him about Lake Monowai, the hunters, and how she wasn’t keen to shoot a deer, but curious to see one.

“Early’s the best time. I normally head up the hill ’round five am. We’d be in the bush just before dawn. We could go in the morning, if you like? Be back by lunch. You’d be on your bike and in Manapouri well before the light fades.”

Dennis switched between channels as Miriam thought it over. Her instinct was to say no, but Miriam was wary of trusting her gut. For her, instinct was often fear in disguise, and she’d made a promise to herself that fear would have no part of this adventure. As she considered, a voice rose from the earth beneath the lodge and whispered to her in a language older than words.

“Okay, why not?” she finally replied.

Dennis smiled, pushed down on the recliner foot until it clicked, and hoisted himself out of the chair to grab another beer.

After the movie, True Grit, they said their goodnights, and Miriam wandered along the moonlit walkway toward her room. The lodge stood empty and silent. She imagined the activity of days past to soften her ghostly reflection in the windows as she walked by; imagined she was the character of Mattie Ross in her quest for revenge. If a fourteen-year-old girl could face down dangerous men with such fierce determination, perhaps courage wasn’t as foreign to Miriam as she’d believed.

She closed the door to her room, bolting it shut for added comfort, though she sensed the real danger lay not outside these walls, but in the morning’s promise.

The alarm went off before Dennis knocked. It was dark, the only light coming from neon numbers on the screen of her phone, and earthshine from the edges of the roller blind.

She was fully dressed by the time he rapped his knuckles on the door. “Miriam… are you awake?”

“Thanks,” she replied. “On my way.”

Under the full moon, Dennis handed her his large camo jacket, grabbed a small blue bag, and headed over to the ute. A faint trail of cologne—sandalwood, she decided—stained the air in front of her. She followed behind as Dennis stretched himself forward into the back of the ute and pulled a long metal box toward him. A rifle lay inside.

“Are you really going to use that? I thought we were just going to look.”

“I never go into the Takkies without my 270. It’s not a done thing. We’ll need protection in case a stag turns.”

She watched as Dennis loaded the rifle with bullets. He stuffed the blue bag with a couple more packets and placed them, and the rifle, back into the metal box. She climbed into the passenger seat as the ute roared into life, headlights on full beam, and they headed into the hills.

Dennis drove the ute up a gravel road for about twenty minutes before slowing to a patch of grass at the roadside. Miriam barely noticed the short bridge crossing, concealed as it was by darkened tussocks, toothed lancewood and towering beech trees.

“Okay, stay close,” he said. “I know a good rutting spot about thirty minutes from here, around that valley up between the trees. Hinds group in the ribbonwood there. That’s where we’ll find your stag, if we’re lucky.”

They stalked through the bush towards the valley. Miriam couldn’t see much, despite the moon and the rising morning light, but Dennis strode forward, confident, experienced. He took large, swift strides, digging his boots into the track as he traveled, stopping occasionally to check for deer prints in the mud, scrapes and rubs on bark. With each step deeper into the forest, Miriam felt something awakening within her: a heightened awareness, as if her senses were expanding beyond their normal limits. She could smell the musk of animals that had passed this way, feel the pulse of sap in the trees, hear the whispered conversations of nocturnal creatures settling into dawn’s embrace.

Light continued to overtake dark. Slowly, the angles, peaks and troughs of the Takitimu mountains took form. It was a beautiful sight of burnished red and pink and blue. She had no idea where they were, but the rising dawn cast a reassuring glance on her soul and put her mind at ease. The forest leaned in closer, protective, as if it recognised something in her that she didn’t yet understand.

Dennis stopped short and gestured for her to get down. “You hear that?” he whispered.

Miriam crouched down as far as she could and listened. A sound. A low-pitched, horn-like call. Somewhere in the bush, quite a distance away. She heard even more: the rustle of small creatures fleeing, the shift of wind through leaves, and beneath it all, a deep thrumming.

Dennis looked at Miriam and mouthed instructions of some sort, then turned back toward the sound. He gently pulled out a pale-coloured horn and blew into it, mimicking the mournful call they’d just heard.

They continued along the track, this time cautiously, eyes scanning left and right. Dennis pointed to rub marks on a nearby tree and blew on the horn again. Such a painful sound, it was, like someone crying out for help. He gestured towards a large fallen tree lying next to a tall stand of beech trees for them to shelter behind.

“Stay still,” he said, his hand cupped around his ear. “Listen.”

She closed her eyes to listen, but to her ear, the forest was anything but silent. It pulsed with intention. Every tree, every fern, every moss-covered stone watching, waiting. If only she were with people she knew, she thought, instead of Dennis. Nothing moved in the world save for her heart, which pounded like boots on hard ground, and the forest itself, which breathed in rhythm with her pulse.

Another call. Low-pitched, like before, but closer now.

Then, Crack!

A clap of sound filled the air, echoing around the valley and mountainside. Dennis dropped to the ground beside her, landing with a thud.

She gasped, cupping her hands over her mouth in shock. Dennis swore and grabbed the side of his chest. Out of nowhere, two men appeared, mid-thirties, in camo shirts.

“What the fuck?” she cried out. “I think you shot him!”

The men looked genuinely shocked. One of them squealed a reply that made no sense to her. They shouted expletives at each other, hands flying this way and that.

Miriam saw that Dennis’ face had softened some and the colour was draining out. She knew a little first aid, but not nearly enough to deal with a gunshot wound. She scrambled over to his side, pulled the hat off her head, and scrunched it up under his. Then she grabbed his hand and pressed it to the wound.

“It went through,” whined Dennis. Miriam wasn’t so sure.

“We’ve got to get help!” she barked behind her.

The hunters looked at each other for a moment, frozen, before breaking into a sweaty laugh. “Fuuuck. Hungover much?” one of them puffed. “Where’s your bloody camo, Dennis? I coulda killed ya!” the other chimed in.

“You know these two?” asked Miriam. When Dennis didn’t answer, she glanced over at the hunters. They looked at Miriam and then at each other. One smirked as the other laughed into his shirt.

Miriam reached toward the blue bag underneath Dennis, but he stopped her.

“Find some kawakawa,” he said, breathing heavily, “small…heart-shaped…”

“Don’t be ridiculous!” she replied. It seemed totally implausible. How far would she need to walk to find kawakawa amongst the thick bracken and fern?

“What about your bag? Didn’t you bring a first aid kit?”

She could see he was weighing something up in his mind. Then he shifted just enough for her to reach the bag and pull it away from under him. Dennis looked away and closed his eyes as she yanked the zip open. Stuffed deep inside the bag, under packets of bullets, a ridiculously ill-equipped first aid kit, some cloth and a flask, was an open pack of condoms.

She pulled the condoms out of the bag and looked at Dennis.

Behind her, the taller hunter chuckled. “Planning on some action, old man,” he said with mirth.

“Dirty bastard,” added the other. “Thought you’d learned your lesson?”

“It’s not what you think,” managed Dennis. “I wasn’t expecting anything.” He began to sob. There was desperation in it.

The forest around them grew still. Even the birds stopped singing. The air itself thickened, pressing down like a held breath. Something wild unfurled within Miriam’s chest, spreading through her limbs like fire through dry grass.

“Hey!” yelled the shorter hunter. “He’s harmless. Wouldn’t do anything you didn’t want to do.”

“Come on, mate,” added the taller one, shaking his head with what looked like practiced sympathy. “Dennis is old school, you know? Doesn’t know how to talk to women anymore.”

“Poor bastard’s just lonely,” the shorter one continued, as if this excused him.

They spoke about Dennis as if he weren’t bleeding on the ground between them, as if this were just another awkward situation they’d help smooth over. Their casual dismissal, their comfortable familiarity with making excuses, made Miriam’s skin crawl. How many times had Dennis done this?

The wind began to pick up, rustling through the canopy above them with an intensity disproportionate to the stillness of before. Somewhere in the distance, branches began to creak.

A deep, panicked sound crawled up from Miriam’s insides toward her throat. The hunters kept talking, their voices growing more defensive, more insistent on Dennis’ innocence, but their words faded as something began to build within her.

“Look, lady, you’re making a big deal out of noth—”

The tingling started in her fingertips, spreading up her arms. Heat flooded her eyeballs, and she felt her jaw unhinge as if making room for something larger.

Out of her mouth came the loudest, most uncontrollable sound she’d ever made. But this was more than a scream. It was a roar, channeled through her human throat. The sound echoed off the mountains and returned transformed, carrying with it the voices of every hind that had ever fled these forests.

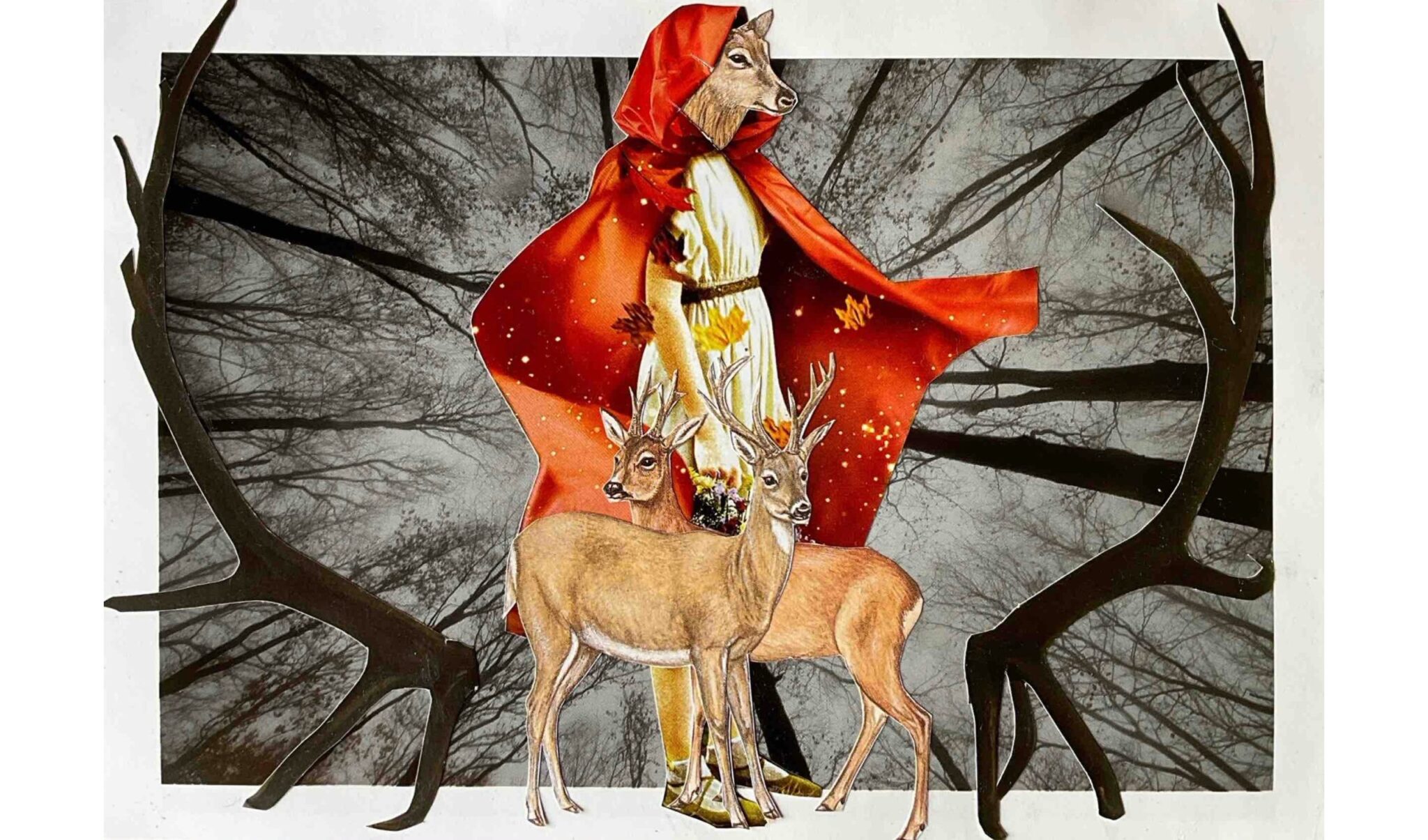

As the roar tore from her throat, Miriam felt her body change. Her spine lengthened and strengthened, and her limbs grew lean and powerful. Her senses sharpened until she could smell fear on the hunters, hear their hearts hammering, feel the tremor in the ground beneath their feet. She retained her human awareness, her human rage, but now it was amplified by a primal and unstoppable fury: the fury of every hunted thing.

The louts stopped talking. Their mouths hung open as they stared at her.

She slammed her transforming foot into Dennis’ side before any sense reached her mind. She kicked him again with supernatural strength, and again. He lay there motionless, as if willing her to continue, tears staining his bulbous cheeks.

The forest had been listening. At Miriam’s roar, the wind rose to a howl that bent the trees nearly horizontal. The ground beneath the hunters began to shift and soften.

“What the hell—” one of them started, but his words were lost as the earth exhaled. Roots erupted from the soil, wrapping around their ankles like grasping fingers.

“This isn’t possible,” the taller hunter said as he pulled frantically at his trapped leg. Moss climbed over their boots up to their calves, spreading with unnatural speed.

The two men struggled against the earth’s embrace, their earlier confidence replaced by terror. They clawed at the roots, tried to pull each other free, but the forest was relentless. It drew them down steadily until their panicked cries were muffled by the moss, determined as it was to silence their voices forever.

Within minutes, the forest floor had smoothed over as if they had never been, leaving only Dennis, bleeding and broken, and Miriam, still caught between her human and deer form but already beginning to understand what she had become.

Miriam felt her body slowly shift back to her human shape, though part of the deer remained in her eyes, in the way she held her head, in her newfound connection to the wild pulse of the forest around her.

The sun was high by now, every tree and fern lit up. The forest glowed with approval, as if it had been waiting lifetimes for Miriam to hear its call. She felt shame trying to rise. Such an idiot, she thought. Who in their right mind follows a stranger into the mountains? But the forest whispered back to her: You trusted because you are learning to trust yourself. You came because you were called. You roared because we needed you to roar.

And then she saw it. Strong and silent. Two gigantic hard antlers, the colour of elephant tusks, with limbs that stretched up to the sky like flames. Its body faced one direction and its head twisted back, looking and listening. The stag tilted its head up and filled the air with its roar; not a greeting, but a declaration of dominance: a call that said this was its territory, its season, its right to take what it wanted.

Light flooded Miriam’s eyes, her heart pumped and every drop of saliva inside her mouth evaporated. But it was not submission that filled her. It was recognition of a familiar threat in a different form.

The stag remained nearby, head lowered now, massive antlers pointed toward her like weapons. Every coarse hair on its trunk bristled.

“Why doesn’t it run?” she questioned.

“Depends how much you…you smell like a hind…” replied Dennis before withdrawing further into his pain.

The stag’s ears scanned the forest, searching for the females it was certain were nearby. Its nostrils flared, and it took a step closer to Miriam, then another.

From the green, they emerged. First one hind, then another, then a small herd of them: graceful, alert, and utterly unafraid. They moved to flank Miriam, taking positions around her.

Miriam felt the roar rise within her again, but this time she was not alone. Her spine straightened, her senses sharpened, and when she opened her mouth, the sound that emerged was joined by the voices of every hind in the clearing.

The stag stopped advancing. Its ears flattened against its skull as it faced not one target, but a united front that would not scatter, would not submit.

It circled them once, testing their resolve, but the herd held firm. Miriam stood at their centre, no longer human, no longer deer, but something new.

Finally, with a frustrated bellow, the stag turned and crashed back into the bush. The hinds remained a moment longer, acknowledging Miriam with gentle nudges before melting back into the forest.

Miriam pulled the cloth from the bag and tied it around Dennis’ wound, her movements efficient but no longer gentle. She leaned the flask next to his good arm and then scanned the forest. She knew they hadn’t ventured too far: roughly thirty minutes, like Dennis had said.

“You’re leaving, aren’t you?” asked Dennis.

“Yes,” she said simply.

“Please don’t. I’ll get you to Manapouri. I promise.” He leaned his head back and sighed. “God, I’m sorry. I’m an old fool. A stupid old fool.”

Miriam took off the borrowed camo jacket and rested it over the sad figure before her. She then gestured for the car keys. Dennis pointed to the zip in his right trouser pocket, turning his head away as she pulled them out. She left the bag and rifle where they lay.

A light breeze followed her as she walked through the bush back in the direction they had come, but every step forward no longer looked the same. Every branch and glimpse of the sky held guidance, kinship. The forest spoke to her in rustles and bird calls, showing her the shortest path back to the bridge. Between steady breaths, she reflected on what she’d just experienced. She thought of how it felt to roar like she had; to transform; to watch the earth itself rise up in protection. She felt as if she could transform again at any moment, felt the deer-spirit resting just beneath her human skin, ready to emerge when needed.

For a moment, Miriam thought she saw a parcel of hinds resting between stands of ribbonwood, but whether they were real or vision, she couldn’t say. What mattered was that she could see them at all.

Relief and recognition flooded her entire body. She’d be at the lakeside village safe and sound by sundown if she carried on. And the forest would always be with her now, and she with it. She had learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the roar that rises when fear proves itself to be wisdom.